BALDUR

Baldur (pronounced “BALD-er;” Old Norse Baldr, Old English and Old High German Balder) is one of the Aesir gods. He’s the son of Odin and Frigg, the husband of the obscure goddess Nanna, and the father of the god Forseti.

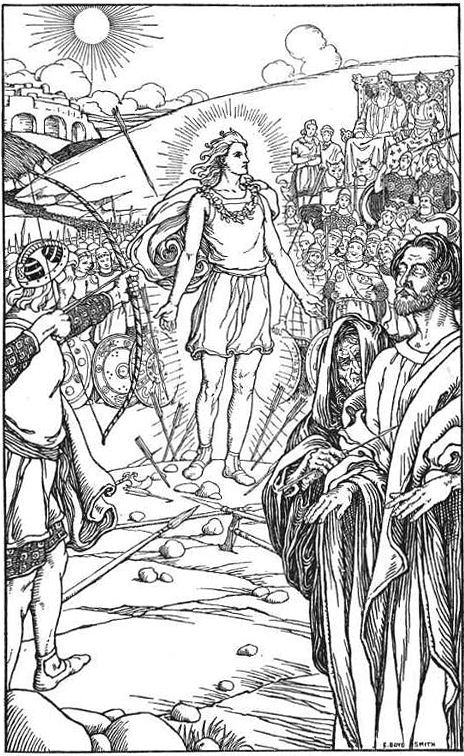

He’s loved by all the gods, goddesses, and beings of a more physical nature. So handsome, gracious, and cheerful is he that he actually gives off light.[1]

The meaning and etymology of his name are uncertain and have been the topic of intense scholarly debate. Numerous possibilities have been proposed, including a derivation from the Proto-Indo-European root *bhel- (“white”), Old Norse bál, “fire,” or a hypothesized word for “lord” common to various Germanic languages. The most straightforward – and probably correct – explanation, however, is that his name comes from the Old Norse word baldr, “bold.”[2][3] Scholars have been reluctant to accept this explanation due to its implication of a warlike character for Baldur. But as we’ll see below, Baldur may not have been as innocent and passive as he’s portrayed to be in the late Old Norse literary source that provides the most extensive description of the god and the tales in which he features.

This literary source is the Prose Edda of the medieval Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson. From this treatise on mythology and poetics comes the most complete account we have of the primary tale concerning Baldur, the story of his death and resurrection. This tale can be briefly summarized as follows:

When Baldur began to have dreams of his death, Frigg went around to everything in the world and secured from each of them an oath to not harm her son. Confident in Baldur’s invincibility, the gods amused themselves by throwing weapons and any random thing they could find at Baldur and watching them bounce off of him, leaving him utterly unscathed.

Loki, the guileful trickster of the gods, sensed an opportunity for mischief. He inquired of Frigg whether she had overlooked anything whatsoever in her quest to obtain oaths. She casually answered that she had thought the mistletoe to be too small and harmless a thing to bother asking for such a promise. Loki straightaway made a spear from the mistletoe and convinced the blind god Hodr to throw it at Baldur. The projectile pierced the god, and he fell down dead.

The anguished gods then ordained that one of them should go to the underworld to see if there was any way Baldur could be retrieved from the clutches of the death goddess, Hel. Hermod, another one of Odin’s many sons, agreed to make this journey, and, mounting Odin’s steed, Sleipnir, he rode down the world-tree until he came to its dark and damp roots, wherein lies Hel’s abode. When he arrived, he found his brother, pale and grim, sitting in the seat of honor next to Hel. Hermod implored the dreadful goddess to release Baldur, and after much persuasion, she replied that she would give him up if and only if everything in the world would weep for Baldur – to prove, in other words, that he was as universally beloved as Hermod claimed.

The whole world did indeed weep for the generous son of Odin – all, that is, save one creature. The giantess Þökk (“Thanks”[4]), generally assumed to be Loki in disguise, callously refused to perform the act that would secure Baldur’s return. And so Baldur was doomed to remain with Hel in her joyless realm.[5]

While this account comes overwhelmingly from one source, bits and pieces of it can be found in earlier Old Norse poetry, and many details of the narrative are depicted on pieces of jewelery dating from before the Viking Age.[6] We can be reasonably certain that the tale as told by Snorri is not only authentic, at least in its general outline, but very, very old.

However, whether out of ignorance or a desire to portray Baldur as a martyr-like figure, Snorri likely omitted a key element of Baldur’s character: a warlike disposition. There’s one other literary account of Baldur’s death, that told by the medieval Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus. As confused and euhemerized (historicized) as this version is, one of the characteristics that stands out is Baldur’s constant eagerness to engage in battle. He’s even depicted as something of a warlord. This, combined with the many kennings that link Baldur’s name with weapons and war in general, suggests that Baldur was much more of an active fighter and less of a passive, innocent sufferer than Snorri makes him out to be.[7]

Other than that, references to Baldur are scarce. He’s mentioned in an Anglo-Saxon chronicle (where he’s given the additional name Bældæg, “The Shining Day,” and described as a son of Woden, the Old English name for Odin).[8] Another brief reference to him can be found in the so-called Second Merseburg Charm from continental Germany, which comes from a manuscript that dates from the ninth or tenth century CE.

While we know relatively little about Baldur due to the fragmentary nature of the sources of our knowledge of pre-Christian Germanic religion, he evidently occupied a position of renown and splendor in the hearts and minds of the Vikings and probably other Germanic peoples as well.

Finally, if you want to learn more about the Nordic shamanism’ conception of learning and experiences in general .

Looking for more great information on Nordic shamanism? While this site provides the ultimate online introduction to the topic, my book Northern shaman provides the ultimate introduction by an Völva and a shaman who are not like the others . I’ve also written a popular list of The 10 Best Norse Mythology Books, which you’ll probably find helpful in your pursuit.

References:

[1] Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Gylfaginning 22.

[2] Turville-Petre, E.O.G. 1964. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. p. 117.

[3] Simek, Rudolf. 1993. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. p. 28.

[4] Ibid. p. 316.

[5] Snorri Sturluson. The Prose Edda. Gylfaginning 49.

[6] Simek, Rudolf. 1993. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. p. 28.

[7] Turville-Petre, E.O.G. 1964. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. p. 115.

[8] Simek, Rudolf. 1993. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Translated by Angela Hall. p. 26.

Create Your Own Website With Webador